NEWSLETTER 135 May 1982

HADAS DIARY

Tuesday May 11 – HADAS Annual General Meeting at Central Library, The Burroughs, NW4, Coffee 8 p.m.; meeting 8.30; slide show afterwards.

Thursday May 13 – Documentary Group Meeting 8 p.m., 21 Village Road N.3. (New members of the Group welcome: please let Isobel McPherson know if you intend to come).

Saturday June 12 – HADAS OUTING to King’s Lynn.

Saturday July 10 – HADAS OUTING to Canterbury.

For the Birthday Year some of the most popular outings of the last 21 years are being repeated.

OTHER EVENTS

Saturday May 22 – Herts. Archaeological Council Annual Conference at Campus West Theatre, Welwyn Garden City 10.30-5.00. Price £1.50 at the door. Subjects Current Archaeological Research in Hertfordshire,and Urbanisation.

Wednesday May 5,12,19,26 at 1.10 p.m. at the London Museum – lectures on Sylvia Pankhurst, Goldsmiths at Work in the 18th Century, Rococo Silver, Hall-marking of gold, silver and platinum.

Thursday May 6,13,20,27 – Museum Workshop at 1,10pm at the Museum.- Subjects:-The Photographic Archive, Preserving our Textile Heritage, Health and Sickness in 16th-17th Century London,

Friday May 7,14, 21 at 1.10pm in Museum – Lectures re Sir Christopher Wren, Subjects – London and the Great Fire, The Rebuilding of the City, and Oxford, Gresham College and the Royal Society 1654-1723.

DAVE KING sends us this note:

The Institute of Archaeology (31-34 Gordon Square) is, after many years, enrolling members. The new membership scheme started in January, 1982,. The annual subscription is £5; it offers these advantages:

1 A free copy of the Institute’s Annual Report.

2 A copy of the list of forthcoming meetings on classical and archaeological subjects. Published three times a year, at the start of each university term.

3 The chance of buying the Institute’s Bulletin and Occasional Publications at 20% discount.

4 Use of the Institute’s library for reference purposes.

There is a separate library subscription for those who wish to borrow books, but “only bona fide reseach students, with an academic referee, are likely to be allowed to borrow books.”

Professor Evans, Director of the Institute, is “very enthusiastic” about members

of local societies taking out Institute membership.

The position regarding the library – which might be the greatest inducement to HADAS members – is more complicated than it seems. Anybody may use the Institute Library, though the librarians reserve the right to refuse permission if it is very crowded.. Institute members would be subject to this condition like anyone else, but it is considered “highly unlikely” that a member would be turned away on Saturdays or in the evenings.

ADDITIONS TO THE STATUTORY LIST

The Borough Planning Officer kindly provides, the following details of recent additions to the List of Buildings of Architectural and Historic Interest:

Crown Public House and 3 lamp standards in front, Cricklewood Broadway, NW2..

151 High Street, Chipping Barnet

Church- House, The Ridgeway, NW7

Nos. 1264-70 (even) High Road, Whetstone

164 East End Road, N3

All are of considerable interest, and HADAS is happy to know that they have been given some protection.

The mention of the lamp standards in front of the Crown is interesting. When it was announced six or seven years ago that the Statutory List for the Borough was to be updated, HADAS recommended the inclusion in the new List of certain items of street furniture – a category which hitherto had not appeared on the Borough List. The updating has not yet been published, although we understand that it has been completed. The lamp standards, we hope, presage the inclusion in it of other items of historic street furniture.

They are described in the Historic Buildings Schedule. like this:

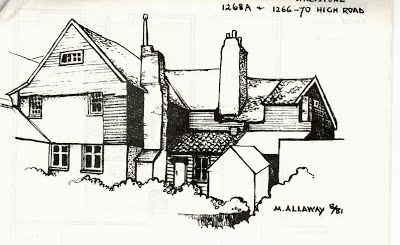

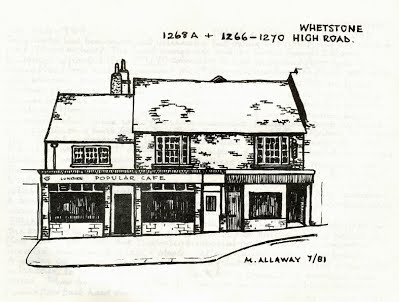

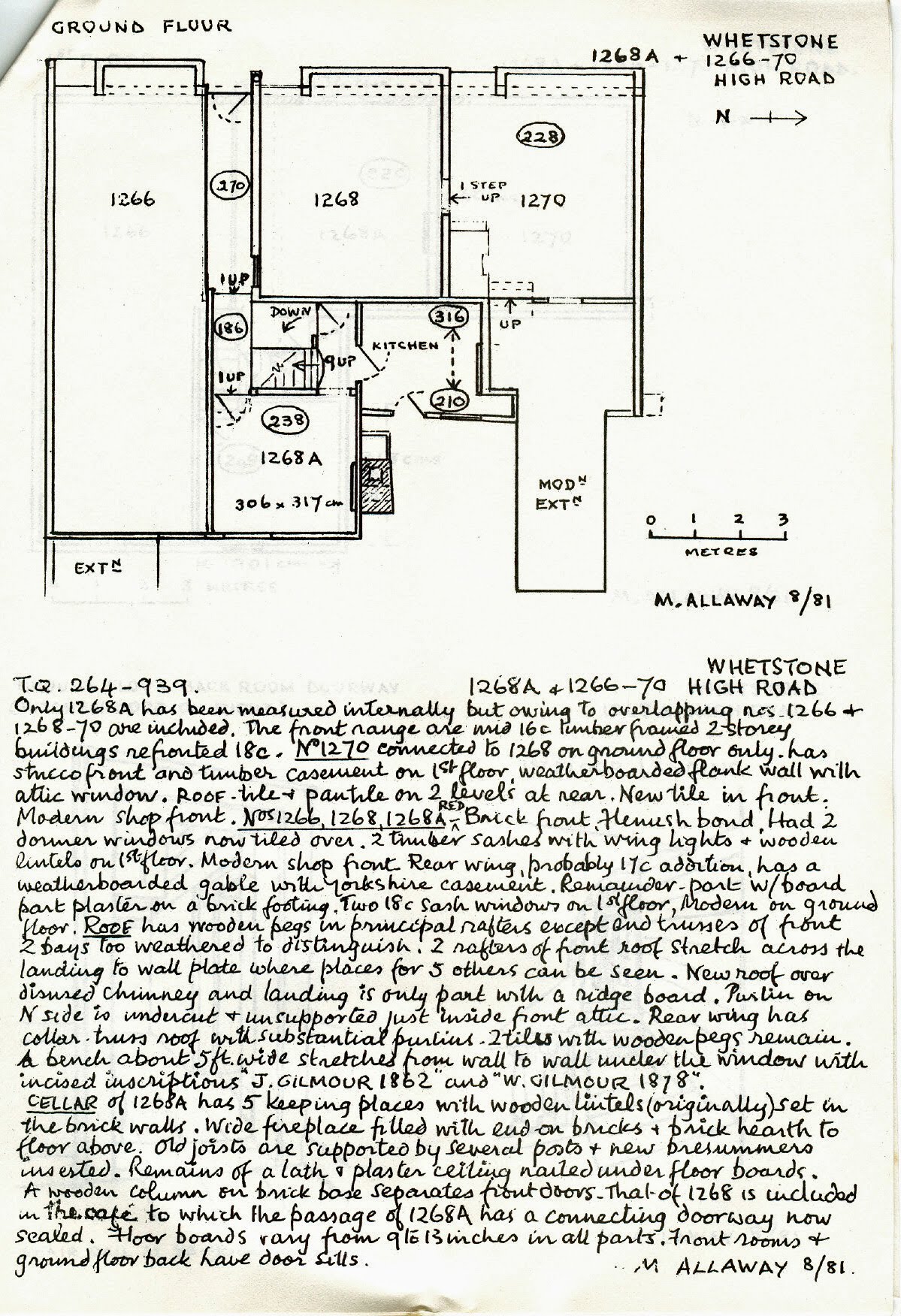

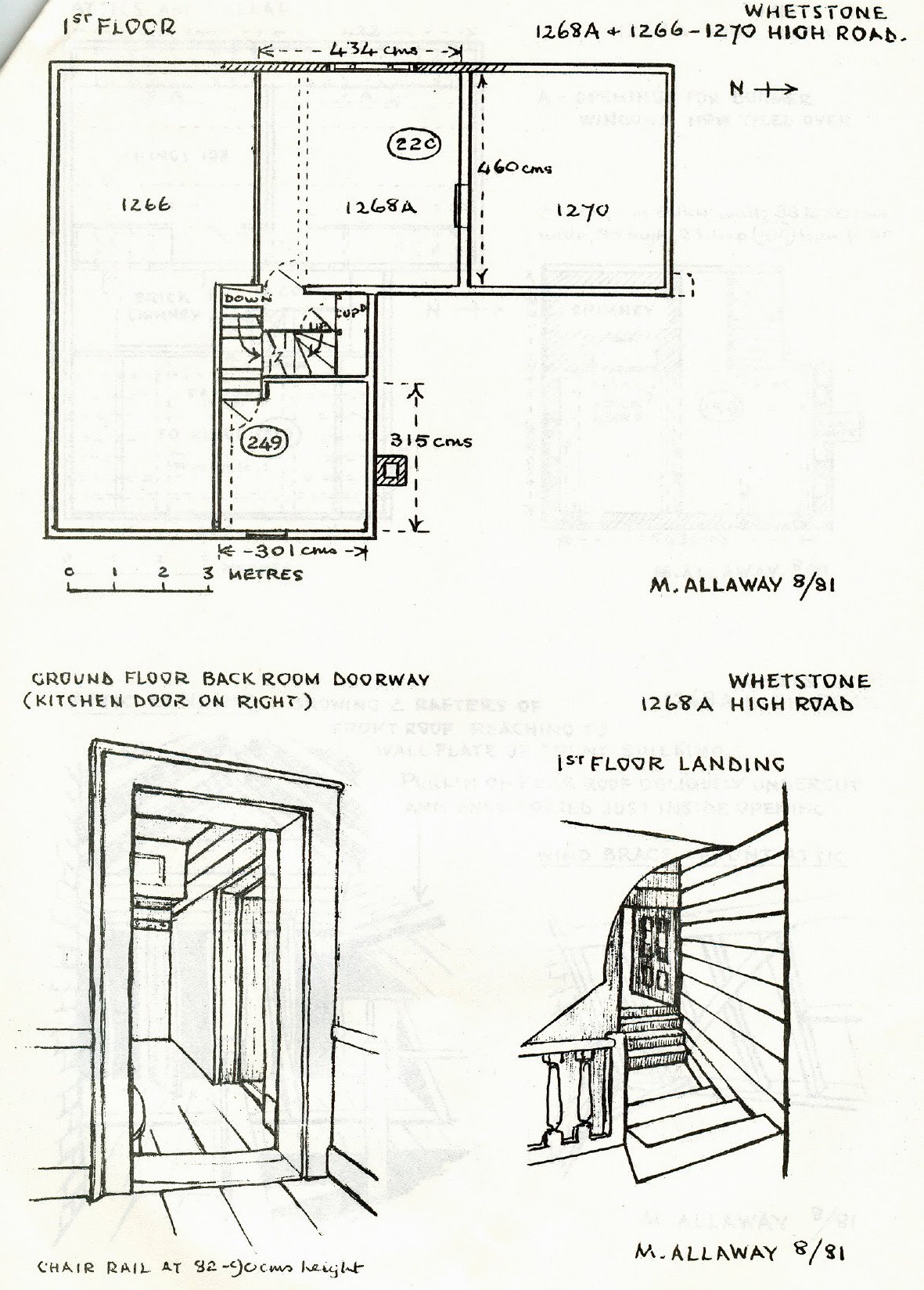

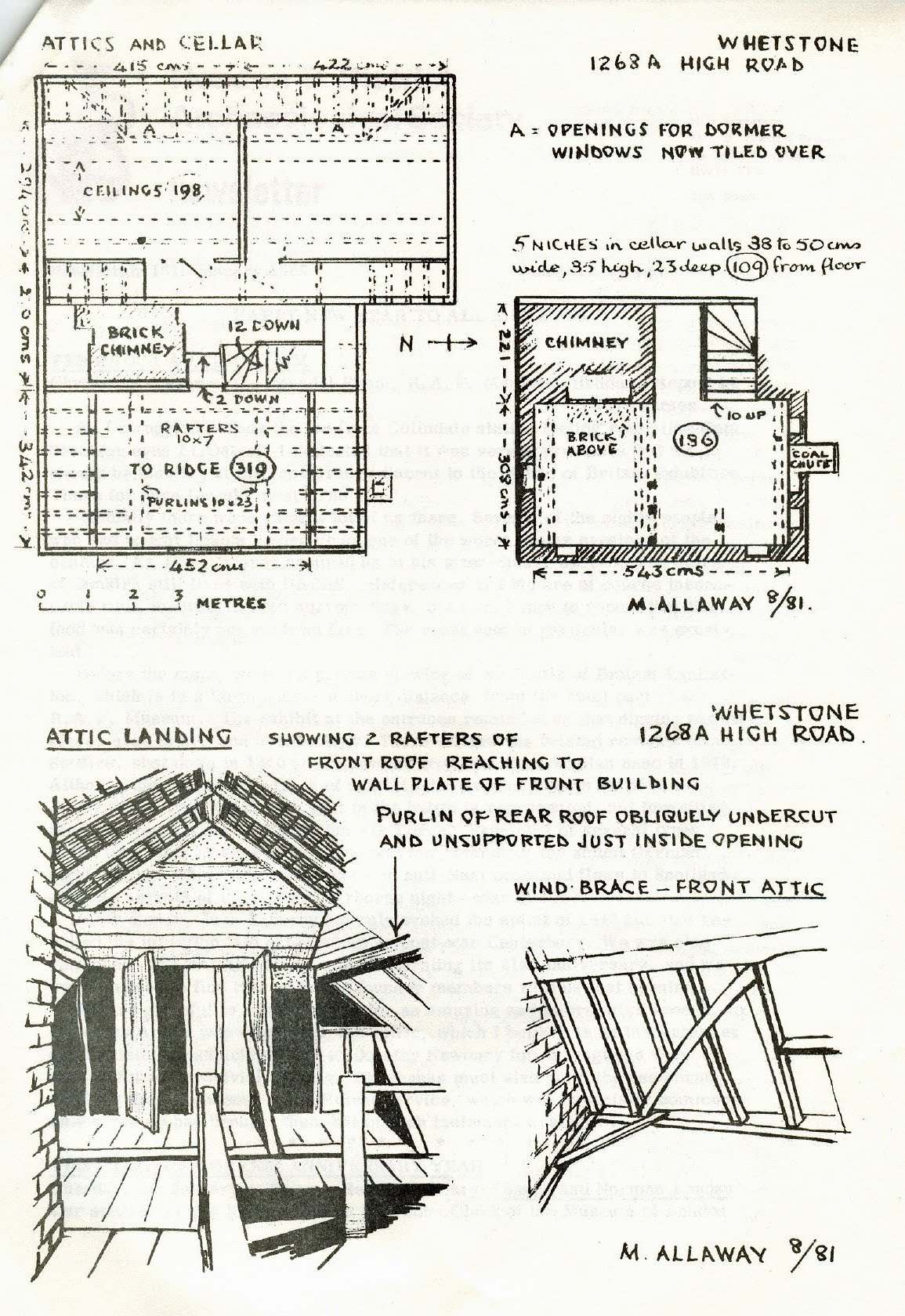

“Early 20th C. Circular tapered granite plinths and cast-iron shafts, whose bases are urn -shaped and supported by four winged iron dragons linked by garlands through their jaws. Above the urn a ball swathed in acanthus leaves supports a tapering quadrangular section leading to a square necking. The lampholder heads have been removed.”Text Box: The group of houses in Whetstone include the one which Mary Allaway recorded: her drawings of it were published in Newsletter No.131. At the time she recording we were told that the group might be listed: it is most encouraging to know that it has been. The official Schedule describes the buildings basically as “mid 16th C. timber-framed, re-fronted in brick during the 18th C”..

Church House at Mill Hill is also part of a group, and is of red brick with a tiled roof, dated 18th C.

We have been interested for several years in 151 High Street, Barnet, for which at the moment there is an application for demolition. The exterior does not look much, but the Schedule describes the building as c, 1700, with a room on the ground floor with wainscoting “of simple 17th C. type with panels of even size, and similar paneling, painted, on the first floor room above and a corner fireplace with a simple chimney piece of the period.” HADAS has, in fact, written to ask the owners if we may record the building, should permission to demolish be given.

HADAS CONFERENCE Report by Sheila Woodward

HADAS members always turn out in force for the Conference of London Archaeologists held each spring at the Museum of London. This year they had a very special reason for attending. The first speaker was our own Daphne Lorimer, talking about our West Heath dig. In the brief space of her allotted 20 minutes Daphne gave the Conference a clear exposition of the nature of the site, the method and scope of the excavation and its ancillary research projects, and an initial assessment and interpretation of the results. The range and quality of flint tools from the site is impressive, and projects such as the analysis of flint-density and the conjoining of cores have added to our knowledge of the manufacturing of such tools. Other work undertaken by HADAS members has included experiments to establish the degree of heat required to produce colour changes in burnt stone, the analysis of charcoal remains from the site, and the study of the pollen profile for the area. Daphne illustrated her talk with some excellent slides, and on display in the Education Department of the Museum was a collection of some of the best of the West Heath finds, beautifully displayed and guaranteed to bring joy to any flint-lover’s heart.

The rest of the morning was devoted to a selection of mini-reports on recent excavations, and research in the London area. One of the liveliest was given by Gustav Milne, who, in his own inimitable style, updated his earlier reports on the Roman waterfront. He even made a tentative claim to have found, in an apparent “return” of an otherwise continuous line of quays, the first fragment of positive evidence for the siting of the Roman London Bridge on the line of Fish Street Hill.

In the afternoon session, entitled “Environment and Man” Philip Armitage resented at interesting study of the Evolution of British cattle from prehistoric to modern times, and Jennifer Hillam talked about the use of tree-ring dating in recent London excavations. Finally, Peter Reynolds, Director of the Butser Ancient Farm Project, expressed some forceful and provocative views on the efficiency of Bronze Age and Iron Age agriculture and the sophistication and affluence of those societies. His message was clear: don’t be fooled by Roman propaganda about conquering the barbarians and improving their standard of living. The prehistorians in the audience applauded loudly!

PREHISTORIC BURIAL RITES IN BRITAIN – PROFESSOR GRIMES

REPORT BY HELEN GORDON

The Presidential Address was a pleasure to hear, Professor Grimes gave us an” expert and exciting survey of prehistoric burials and the information they provide about the central role of death in the life and religion of the people. In the course of the evening he raised many questions: What were those people doing when they shoved their contemporaries’ bones into these tombs? Why did they select and position certain bones, and tuck little ones into nooks and crannies, and were they trying to keep the bones safe from the living world, or the living world safe from the world of the dead when they sometimes made the entrances so small that the skeletal remains could hardly be got through the holes? What were the ritual functions implied by the architecture, and why did they sometimes continue to use an architectural feature when apparently its function had fallen into disuse? What kind of people were selected to be (partially) preserved in this way?

Professor Grimes demonstrated the nature of these problems by illustrations of burials mainly in Wales and the west of Britain, dating from the Paleolithic to the Bronze Age. Little is known of the Paleolithic or Mesolithic customs in Britain, apart from them “Red Lady of Paviland” (thought to have been a Romano-Briton when first excavated by William Buckland in 1823, but later C14-dated at 16,000 BC; her red-ochred bones are actually those of a young man of 22), and undated skeletons in caves which may have been Mesolithic But with the advent of the Neolithic farmers who spread across Europe from the east from 8,000 B.C. onwards and reached the extreme west about 4,000 BC, chambered tombs appeared in many parts of Britain.

It is unfortunate that most prehistoric tombs were rifled by tomb robbers, or excavated before modern methods were known, and often the contents were lost, But accumulated evidence, confirmed by the few untouched tombs such as Stanhill, shows that they were in fact osstaries, usually containing partial. remains of numbers of individuals of both sexes and any age. They remained in use over periods as long as .1000 years, and the bones were often selected and arranged; usually only the last. individual to be inserted appeared to be intact.

The architecture of the tombs, though based on the same general design,shows considerable diversity. The tomb Tinkinswood demonstrates the normal wedge-shaped mound with the concave facade and forecourt, but the capstone is immense and weighs 70 tons, and the entrance is at the side. It is possible that the front walls had been covered with earth; in some cases even cap-stones may have been covered so that the location of the chamber was secret. On the other hand some portal stones have been so carefully chosen that it is improbable that they were covered. Entrances were sometimes blocked so as to be unrecognisable not only from the outside but also from the inside, and some entrances were made very small by placing stones at an angle, or cutting “port-holes” in blocking stones. Sometimes a large stone blocked the entrance which could be moved to re-open the chamber; this can be seen at Pentre Ifan where the central stone in the portal stands short of the cap-stone. But in another case the central stone, though free of the cap-stone, was itself so blocked with packing stones that the whole structure would have collapsed if it has been moved; change of use had not brought change to the traditional method of construction. These variations give the impression of a need to separate the living from the dead,

Earthen long-barrows, which usually contain some form of timber ossiary, bear a resemblance in their overall pattern to the stone-built tombs. The two types show regional distribution, though they co-exist in some areas, and some were combined in different phases. Earth barrows sometimes had stone platforms for exposure, and it is thought that the bones were brought in one operation.

With the onset of the bronze age in the second millenium BC, a new circular form of burial mound appeared. The mound varied in size up to 80 ft, in

diameter, and the primary burial was usually in the centre,sometimes in a pit, or on the land surface, or in a kist; additional burials might be inserted at the same time or later. The barrow might be defined by stone rings, or ditches. Standing stones can mark a burial site, and when excavated other stones may be revealed in some ritual position; in one example a large number of small stones set on edge accompanied a crowded pit burial.

Professor Grimes with his excellent slides then demonstrated a richness in variety on the basic theme too complex to be described here in detail, and he pointed out that over all there appears to be a continuity of purpose; an area of interment remains in some way special, or sacred, even though the sepulchral monument may be changed or augmented over an immense period of time, across cultural boundaries, as indicated by a possibly Christian extended burial near a barrow, and an Anglo-Saxon cemetery near six round barrows and a long barrow.

If this is Professor Grimes’ first address to HADAS since he became our President, it is to be hoped that he will allow his Presidential duties to become a little more onerous, and that it will be less than 17 years before we hear him again.

A TRIAL TRENCH IN THE GARDEN OF 14 CEDARS CLOSE, HENDON NW4

REPORT BY PERCY. REBOUL ON THE DIG OF APRIL-OCTOBER 1980

1. Introduction

In April 1980 the Hon. Secretary of HADAS was contacted by Mr. Michael Miller, owner of 14 Cedars Close, Hendon NW4. He stated that, during the course of excavating a 60 cm. wide trench on the lawn of his back garden, to take new land drains, an “old wall” had appeared and he would like it investigated. A cursory examination, showed the structure to be of potential interest, and digging started immediately following agreement with Mr. Miller.

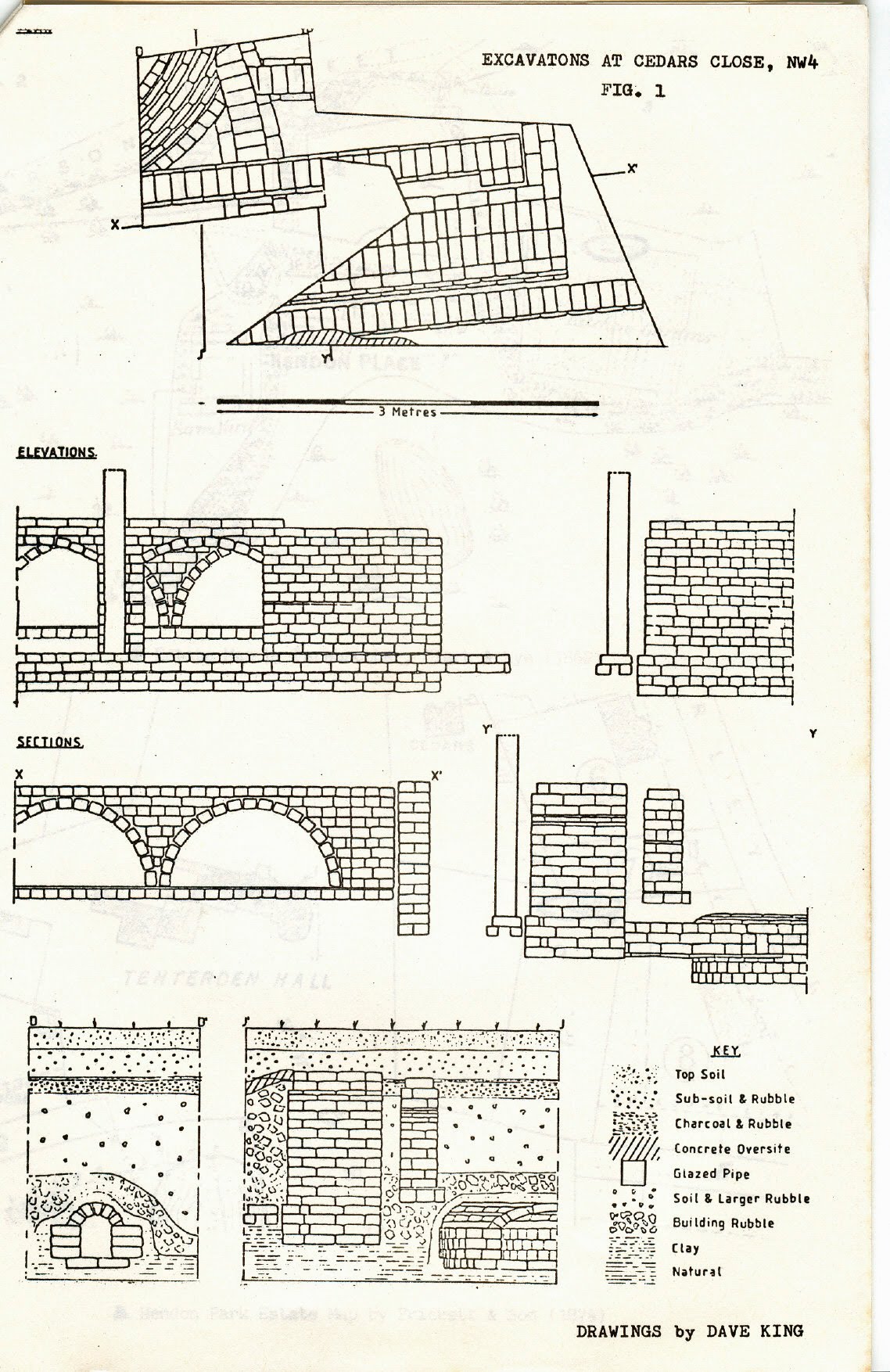

For a number of reasons it was decided to limit the investigation to a trial trench. The wall was adjacent to a valuable cherry tree whose root system intermingled with the structure; the garden contained cultivated flowerbeds and recently-planted saplings which could not be disturbed; there would have been some problems with locating a large spoil heap and the owner was anxious to complete the land drainage system as soon as possible. The decision was therefore taken to dig two small trial trenches, one north and one south of the brick wall which had been discovered. The final (and unusually asymmetrical) configuration of the trench was the result of the above factors. (See Excavation Plan, fig.1).

2. Documentary Research

The Site, The Cedars Close area has always been recognised by HADAS as of potential archaeological interest, evidenced by the “Abbot’s Bower” blue plaque, commemorating “the country seat of successive Abbots of Westminster,” erected although the precise position of the medieval manor house is unknown) at the junction of Cedars Close and Parson Street,*

At the time this Report is published, the plaque has vanished. The Borough Planning Officer assumes that it has been stolen. He is investigating the possibility of replacing it. In brief, this interest centres mainly around:

(a) The first manor house, timber-built in 1325/6 as a country retreat for the Abbots of Westminster

(b) The rebuilding of the original house around 1550 by the Herbert Family

(c) The final re-build in the 1720s when it was known as Hendon Place. The first Baron Tenterden, Land Chief Justice, bought the estate in the early 19th C., renaming the house Tenterden Hall

(d) The demolition of Tenterden Hall in 1934 to make way for the present Cedars Close

3. Evidence from Maps

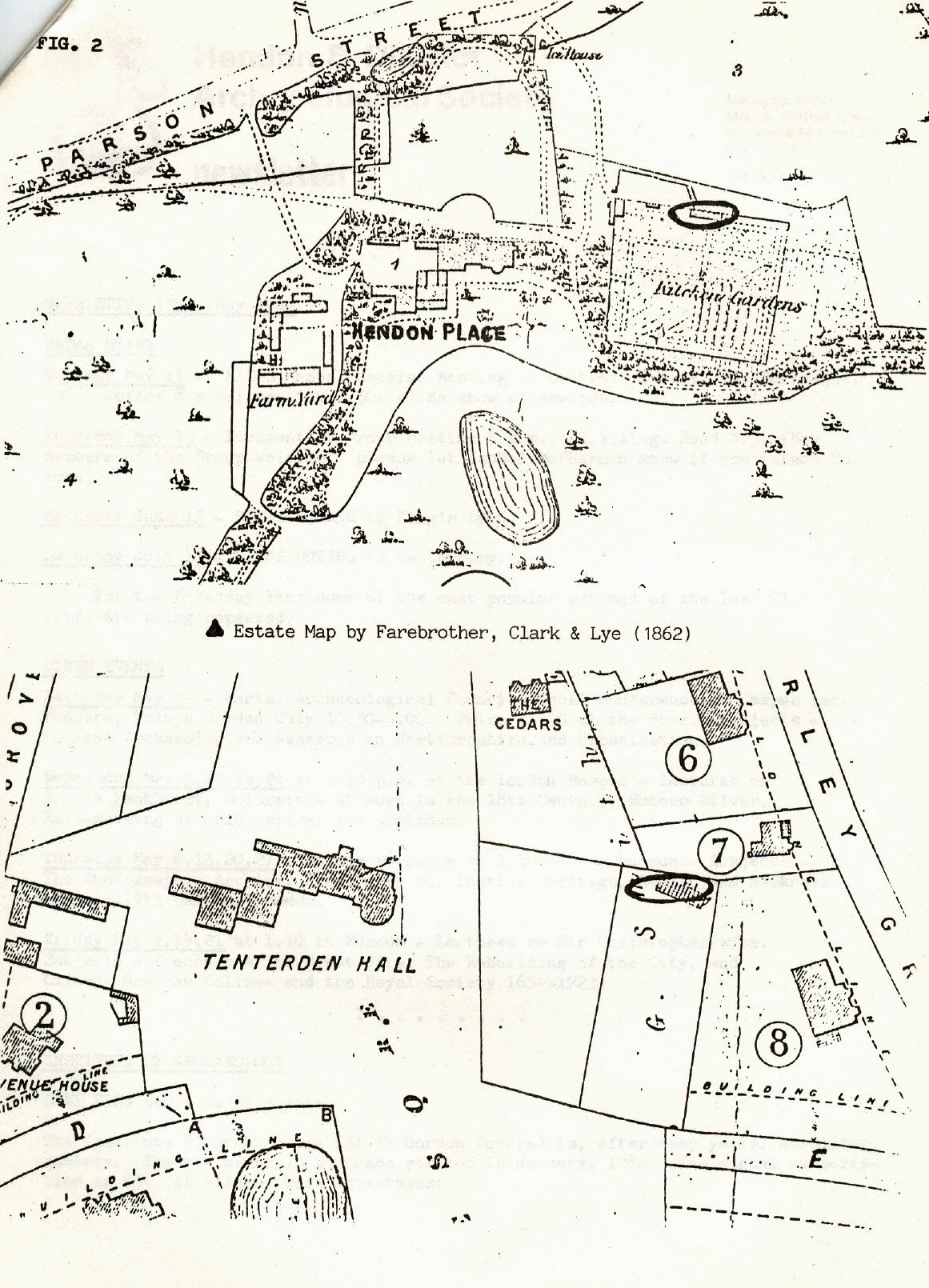

Concurrent with the opening of the trial trench, HADAS members Dave King and Edward Sammes investigated evidence from OS, tithe and estate maps, —Dave King examined:

25″ OS maps dated 1863, 1904 and 1956

Tithe map of 1836

Estate map of 1796

His conclusion, making due allowance for the differing scale of the maps and overlaying/superimposing against the most recent large-scale OS map, was that the find was probably the north section of the walled kitchen garden of Hendon Place as outlined in the 25″ OS map of 1863. More specifically, it appeared to be a greenhouse or glass structure built against the garden wall.

Further evidence for a greenhouse structure was confirmed in the 1836 tithe map provided information on earlier forms of cultivation. The tithe book of 1836 describes plot 928 as “a walled garden” and plot 929 as “melon ground, gardeners’ cottages, sheds, etc. Based on nothing more than its romantic imagery, the site was promptly christened “the melon house”.

3. Evidence from Excavation

The South Trench

This trench, the first to be dug, was south of the brick structure. The north face of the trench was the structure itself and the south face was the land drain trench excavated (west to east) by the builders.

The removal of 20 cm of topsoil, which included the existing lawn, revealed that the brick structure was 80 cm wide – substantial and mode from excellent bricks very well built and pointed. A 10 cm thick concrete raft had been constructed running from the rebated edge of the south face of the brickwork in. a southerly direction (see Section J, fig.1). The extent of this raft or its use is not known. It was probably constructed c. 1934 as part of site levelling. operations – possibly to remove the danger of subsidence. An interesting feature was clay land drains placed on top of the concrete raft subsequently covered with the 20 cm of top soil. With the breaking through of the concrete raft, the springing of a well-built brick arch was quickly revealed. The section drawing shows details of this feature and another adjacent arch. Natural clay was found at a depth of 180 cm. The brickwork throughout was in excellent condition and of high quality workmanship, its structure having been covered with an ash like backfill. There was no stratification.

Small finds in the South trench included:.

(a) Substantial quantities of mid to late 19th c. glazed pottery, the sherds being mostly small. The best piece was a complete base of a Spode teacup but as the infill was probably brought from another site and dumped, these finds are of no value for dating.

(b) Quantities of oyster shells

(c) Various metal objects such as a pair of large iron gate hinges, hand-made nails .and part of a scythe blade.

(d) Late 19th c. clay. ipe bowl and various pieces of stem.

Two features; apart from the brickwork itself, are worthy of note. The first was the brick drain at the base of the wall and running parallel, to it (see Section J). This comprised brick sides. and capping but no tile for the base natural clay was used to run the water away. The second was a modern-looking 9″ diam. brown glazed-ware sewer pipe running vertically from 20. cm down from topsoil to the brick drain mentioned above. This pipe was presumably installed c. 1933/4 to drain the new topsoil used in levelling the site prior to building (see Fig. 1 Section Y) It may also indicate that the ash-like backfilling south of the wall was also dumped in 1933/4 as part of levelling operations.

The North Trench

This provided nearly all the evidence for our conclusions. Its north face was some 2 m from what today is the back wall of the Millers’ garden – this was probably originally the north wall of the kitchen garden. Its south face was the north side of the brick. structure.

At 40 cm down a clearly defined “destruction layer” appeared (Fig. I, Section J). This was 20 cm thick and comprised burnt wood, charcoal, quantities of broken glass panes, terracotta earthenware gardening pots of various dimensions, metal glazing clips, putty fragments, lead strips and a long shanked screw-eye of the type used in greenhouses to secure the wires along which climbing plants such as vines are trained.

Some surprise was felt when, just below this layer, a second arched wall was found. (Fig.1 Section X). The structure was much less substantial than that uncovered in the south trench, and its workmanship was inferior. It was also earlier and may well have been associated with the growing of exotic fruits before the popularisation of the greenhouse in mid-Victorian times. No dating evidence was found, however, and this must remain speculation.

About 140 cm down two drains (at different levels and lines of direction) of’ good workmanship were uncovered; One was built entirely of brick, the other being brick and tile. These fed into a well-built brick culvert (plan view and section D Fig. l). The drains were constructed from hand-made bricks measuring 8½”x 3½” x 2½” with all courses bonded in lime mortar. Both were capped in unmortared bricks laid horizontally. Their junction with the culvert was of fine workmanship.

The brick culvert was exceptionally well-built. It came in from the west side of the trench and bent 900 into the direction of north (Fig. 1, Sections D & J). The brickwork, together with that of the feeder drains mentioned above, was similar to that of the arched wall found in the south trench and may be assumed to be contemporary. The culvert was covered by a substantial layer of large brick rubble, including conglomerates of several bricks. Of particular interest was the finding of several Tudor bricks among this random layer, which may possibly indicate that the builders had used bricks found on the site as a backfill or soak-away.Is this perhaps our first albeit speculative, evidence of the Tudor manor house at Hendon?

Several bricks were removed from the rounded top of the culvert to reveal the structure inside. A substantial deposit of silt, about 20 cm thick, lay on the base of the culvert. Sieving revealed nothing more than a few animal bones, small pieces of flat glass and more small sherds of 19th c. glazed pottery. The opportunity was taken to “rod” along the length of the culvert. It stopped at 2 m in a northerly direction, the rods almost certainly striking the garden all mentioned earlier.

Rodding in the westerly direction was inconclusive in the sense that at 20 m we ran out of rods, so it may well be of very substantial length. Possibly the drain originally ran from the house for what purpose we do not know, except that it was certainly not for sewage or foul water. It may have been part of the drainage for the small lakes abutting Parson Street (shown on the 1862 Estate map, Fig.2). The most obvious use, however, was as part of the drainage of the building which stood above them.

Small Finds from the North Trench

The finds discovered in the destruct layer have already been described above. Small quantities of mid to late l9th C. glazed pottery sherds were found adjacent to the brick drains, otherwise nothing of significance.

The most magnificent find, however, occurred at a depth of 37 cm — a cast iron pierced grill measuring 1178 x 457 mm. The grill, similar in type to those seen today in greenhouses where, typically, they are used to cover floor gulleys housing the heating pipes, was inscribed with the name “J. Weeks, Chelsea.” This firm was one of the most illustrious companies employed in greenhouse building. They started business in 1808 and finished in the 1960s, and are referred to in all the catalogues and treatises on the subject of “hothouse engineering.”

Manufacturers of horticultural buildings flourished in the period 1860-1880. Weeks & Co. were a leading London manufacturer located at Kings Road, Chelsea. They had a long tradition of supplying glasshouses and had a “winter garden” next to their works from which could be provided a complete package deal – iron and wood glazed structures, heating and ventilating equipment and even plants. Horticultural magazines of the time are filled with Weeks’ designs including, for example, glasshouses at Hampton Court and the Winter Garden at Folkestone.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

The limited nature of this trial dig makes it doubly unwise to draw too firm conclusions, but a reasonable hypothesis might be:

(a) Lord Tenterden bought the house in the 19th c. It would be reasonable for him, as a wealthy man, to improve both house and garden. The 1936 tithe map certainly shows a number of interesting features in the Garden complex, and the reference in the tithe books to “melon ground etc.” suggest that his lordship may.well have indulged the current passion for growing exotic fruits and plants; It may well have been at this time that the earlier arched wall-found in the north trench was constructed. Associated would have been the thinner type of glass found in the trenches. It is known that arched walls were used around this time to grow vines, the root systems being trained through the arches and the branches along the walls.

(b) Taxes on glass and building materials were removed in the 1840s. This, together with the impetus given to glasshouse building by the 1851 Crystal Palace, resulted in a golden age of greenhouse cultivation. Apart from the buildings themselves fuel and labour were plentiful and cheap; the middle and upper claases had money to indulge their horticultural interests and fantasies and the use of cast iron to make sophisticated heating systems was developed and marketed with considerable skill. In all of this, however, essential ingredients were plentiful heat, water .and good drainage.

(c) Sometime between 1862-741 as the estate maps reveal, the Tenterden estate was revamped and the large walled kitchen garden shown on the earlier maps was replaced by a substantial greenhouse structure. J. Weeks & Co. of Chelsea, one of the leading “hothouse engineers” was called in to carryout the work. They would certainly have built the glasshouses and associated engineering work, and it is possible too that they constructed the drainage. system comprising brick and tile drains feeding into a main culvert. This would account for the highstandardof work involved.

(d) The 1914-18 war, with shortage of fuel and manpower, would have been in part at least responsible for the decline of the complex. Between then and 1933/4, with the added problem of severe economic depression plus more sophisticated methods of importing exotic fruits, the greenhouses would have fallen into disuse and disrepair. They were finally demolished around 1934, together with the big house itself, to make way for Cedars Close. At the time of demolition, Tenterden Hall was a boys preparatory school.

All the evidence points to a greenhouse complex of some kind. One question however arises: why would the walls be of such massive dimensions? At 80 cm thick they would have supported the manor house itself!

A metal detector was run over the area west of the trenches along the presumed route of the culvert. There were several substantial readings and it could be that parts of the boiler system or more cast iron grills are just beneath the surface.