Number 579 June 2019 Edited by Melvyn Dresner

HADAS DIARY – LECTURE AND EVENTS PROGRAMME 2019

Tuesday 11th June 2019 7.30 pm Annual General Meeting, Jo Nelhams

This year’s meeting will be followed by a lecture from our President, Harvey Sheldon, entitled

“Imperial Rome’s north-west frontier: can it explain Britannia and Londinium’s role within the

province?” We hope that many members will attend showing their support for those who

voluntarily give their time by standing for the committee and organising HADAS. Without them

there would be no society. Tea and coffee at the meeting will be free of charge. If you are unable to

attend, please send your apologies to Jo Nelhams by email (jo.nelhams@live.co.uk) or phone (020

8449 7076) Please note early start time.

Saturday July 27th 2019 SECRET RIVERS – at the Docklands Museum

HADAS is planning a visit to this exhibition revealing the history of London’s forgotten rivers. As

announced at our last lecture, Deirdre Barrie and Audrey Hooson have proposed an outing to the

Docklands Museum on Saturday 27th July. The Museum is staging a free exhibition starting from

24th May called “Secret Rivers”. If you have a bus pass, your transport is also free. Quoting from

the Museum’s publicity:

“Secret Rivers uses archaeological artefacts, art, photography and film to reveal stories of life by

London’s rivers, streams and brooks, exploring why many of them were lost over time.

“The intriguing histories of the River Effra, Fleet, Neckinger, Lea, Wandle, Tyburn, Walbrook and

Westbourne will all feature in the exhibition. Each river will highlight a broader theme such as

poverty, industry, development, effluence, manipulation, activism, sacred association and

restoration.”

The museum requests that groups book in advance, so although we require no deposit, rough

numbers are need. There is a coffee bar at the museum and other places for lunch close by, or you

can bring your own sandwiches. Will meet either at Bank Station DLR platform at 10.30, for West

India Quay or at 11.00 in the museum coffee shop. Please contacts Deirdre Barrie (020 8367

0922) dlbarrie@tiscali.co.uk or Audrey Hooson AudreyHooson@icloud.com

HADAS 2019 Long Trip. Monday 23rd to Friday 27th September 2019. We have booked the

hotel for our long trip in 2019. Details will follow in due course. The hotel is: Best Western

Aberavon Beach Hotel, Aberavon Beach, Port Talbot, SA12 6QP.

Tuesday 8th October 2019: From Crosse & Blackwell to Crossrail – MOLA excavations at

Tottenham Court Road 2009–10 by Lyn Blackmore.

Tuesday 12th November 2019: Shene and Syon: a royal and monastic landscape revealed by

Bob Cowie.

Lectures are held at Stephens House & Gardens (Avenue House), 17 East End Road, Finchley, N3 3QE, and start promptly at 8 pm, with coffee / tea afterwards. Non-members admission: £2;

Buses 13, 125, 143, 326 & 460 pass nearby and Finchley Central station (Northern Line), is a 5-10 minute walk away.

History of Clitterhouse Farm, Hendon Roger Chapman

The inaugural memorial lecture for Dorothy Newbury MBE (15th February 1920 – 13th February 2018) was given by Roger Chapman on 12th February 2019.

Clitterhouse has been known by many names – Clater’s House, Clutterhouse, Clitherow and Clytterhouse being some of them. The Clitter part of Clitterhouse is thought to originate from the word ‘clite’ or clay and has been roughly translated to mean ‘clay house’. The early history of Clitterhouse Farm is vague, clouded in mystery, tied up in disputed Charters and ripe for historical myth making. Earthen banks identified by aerial photography, were suggested to form a moated enclosure and defence line against Viking invasion across to Oxgate lying on the western side of the Edgware Road. In the past it was speculated that the Farm may have been a Viking raided homestead, blackened by fire, and then restored as: ‘A house of clay … of such thickness of wall that even a modern bullet would scarcely penetrate.’

From these ashes, Clitterhouse, the clay house ‘probably arose.’ It is a great story but evidence to support it is thin. The land is not mentioned in the Domesday Book of 1086 though Hendon is mentioned. In the Domesday Book (1086) it is estimated that Hendon had a population of 250 with enough woodland to support 1,000 pigs. By 1321, the time of the Black Book, there was still a great deal of woodland in existence, but less than at the time of Domesday. Clitterhouse Manor starts with Robert Warner, lawyer and one time under Sheriff of Middlesex. In 1439 he granted the land to St. Bartholomew’s Hospital on condition that a Chaplain and four youths would pray for him. Green, a son-in-law of Robert Warner secured a payoff from the will, on payment of a sparrow hawk, of sixty acres of land, six acres of pasture and 36 acres of woodland in Clitterhouse. Not a bad transaction for a sparrow hawk. The manor was eventually released to the hospital in 1446. The Farm remained in the ownership of St Bartholomew’s until 1921. The hospital’s property in Hendon was augmented in 1446 by two nearby estates granted by Henry Frowyk and William Cleeve, Master of the King’s Works. The first, called Vynces, lay north of the Clitterhouse estate and the second, Rockholts, lay south of the road to Childs Hill.

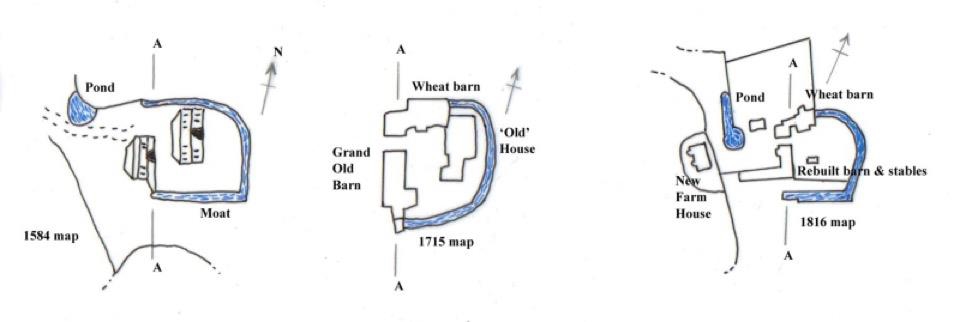

A survey in 1584 of Clitterhouse Farm “now in the tenure of Edward Kempe” was undertaken by Ralfe Treswell. At this time the farm was over 200 acres comprising 18 fields, each with a perimeter woodland strip, 2 woodlands, an orchard, farmhouse, outbuildings and a moat. Emphasising the importance of woodland, at the time, the survey identifies 1295 ‘timber trees’ on the farm. Timber was the building material of choice and would also be used for fencing, wattle work and in large quantities for fuel. The farm land extended to the ‘West High Waie’ (Edgware Road) and was bordered to the south by land belonging to the Abbey of Westminster. To the north the landowner was Sir Roger Cholmeley, founder of Highgate School. Primary access to the farm was via a trackway from a feature called ‘Clitterhouse Cross’, presumably a wayside cross or Calvary, on the ‘West High Waie’ and this ran past fields called Great Rockholts, Noke Field and Great Camp to the House and then a track ran (roughly on the alignment of Claremont Road today) past Bente Field, Hill Field and Great Vince, out past Whitefield Gove which was on Cholmeley’s land. Edward Kemp occupied the farm in 1610 when his house was broken into and a woman’s violet coloured gown worth 40 shillings and other personal goods were stolen. Three men and a woman were charged. Two of the men were ‘at large’, the other man pleaded not guilty and was acquitted. The woman, Joan Eliott, stood mute and for that reason was condemned to a punishment called “peine forte et dure”. She was laid on her back under a great weight and on alternate days was fed small quantities of bread or water until she died. One reason she may have stood mute is by

not pleading she would avoid forfeiture of property. This type of harsh punishment was abolished in 1772, though its last use was in 1741. Thomas Kempe was resident during the time of Cromwell and in his 1667 will left the lease of the farm to his son, Edward, with all the ‘corn, hay, cows, sheep etc.’ Edward continued at Clitterhouse until 1674 when he responded to a ‘hue and cry’ raised against highway robbers who had held up the mail coach on the Windsor Road and then fled across country from Hanwell to Harrow. All available able men in Hendon mounted their horses and tried to cut off the miscreants. Edward Kempe was to the fore and as he approached them, on the narrow lane leading to Hampstead Heath, they fired and he fell from his horse with a bullet in his side. He survived for 24 hours. The villains were caught, taken to Newgate gaol, and eventually executed. The body of their leader, Francis Jackson, was hung in chains on a gallows tree between the Heath and Golders Green. The Kempe’s kept a connection with the Farm until 1794.

By 1715 a new plan of the Farm, prepared by Robert Trevitt, shows a much reduced woodland area, only 19 acres out of 203 total. Most of the woodland strips surrounding the fields had been grubbed out and a further 7 acres were lost by 1753. This plan also contains a superb drawing of the farmyard in 1715 showing timber framed and weather boarded buildings making a tight group around the farmyard. John Roques 1746 plan ‘10 miles around London’ shows a range of five farm buildings called ‘Claters House’.

The decline of woodland continued and in a survey of agriculture un 1794 hay was a key crop and in the neighbourhood of ‘Harrow, Hendon and Finchley there are many hay barns capable of holding 30 to 50 and some even 100 loads of hay’. Hendon by the time of the Tithe apportionment map of 1843 was 91% (7330 acres) in meadow and pasture use with just 0.04% of land (283 acres) in arable production and a miniscule 40 acres (0.005%) woodland. Clitterhouse Farm, now tenanted by Jonathan Caley, reflects this with the majority of fields shown as meadow and only some as arable. In the 1860s the coming of the Midland Railway Company cut Clitterhouse Farm in two (north to south) and led to the building of Claremont Road. The land west of the railway line became Brent Sidings in the 1880s. From 1876 until 1915 the Brent Gas Works supplied stations from Mill Hill to St Pancras, including the Midland Hotel and the railway workers cottages called Brent Midland Terrace (1897). Between 1884 and 1913, the influential suffragette Gladice Georgina Keevil (1884 – 1959) lived at Clitterhouse Farm. At age 6, she won a prize for her clay modelling at the local kindergarten. In February 1908 she was one of those arrested with Emmeline Pankhurst in taking part in a demonstration outside the House of Commons.

The decline of woodland continued and in a survey of agriculture un 1794 hay was a key crop and in the neighbourhood of ‘Harrow, Hendon and Finchley there are many hay barns capable of holding 30 to 50 and some even 100 loads of hay’. Hendon by the time of the Tithe apportionment map of 1843 was 91% (7330 acres) in meadow and pasture use with just 0.04% of land (283 acres) in arable production and a miniscule 40 acres (0.005%) woodland. Clitterhouse Farm, now tenanted by Jonathan Caley, reflects this with the majority of fields shown as meadow and only some as arable. In the 1860s the coming of the Midland Railway Company cut Clitterhouse Farm in two (north to south) and led to the building of Claremont Road. The land west of the railway line became Brent Sidings in the 1880s. From 1876 until 1915 the Brent Gas Works supplied stations from Mill Hill to St Pancras, including the Midland Hotel and the railway workers cottages called Brent Midland Terrace (1897). Between 1884 and 1913, the influential suffragette Gladice Georgina Keevil (1884 – 1959) lived at Clitterhouse Farm. At age 6, she won a prize for her clay modelling at the local kindergarten. In February 1908 she was one of those arrested with Emmeline Pankhurst in taking part in a demonstration outside the House of Commons.

Keevil’s picture was taken in 1910 by Colonel Linley Blathwayt (died 1919) at Eagle House near Batheaston, Somerset. Where she (and other suffragettes) went to recover and celebrate a prison sentence for the cause. Here with shovel in hand after planting a tree.

By the First World War, Clitterhouse farmland was much reduced in size, becoming a dairy farm, which was 100 acres in extent and had “40 cows in full milk” producing 10 quarts per day on average. Land had been for Hendon sewage works in the 1880s, and to Hendon fever hospital (1890-1929). The estate remained the property of St. Bartholomew’s Hospital until 1921, when it was sold to the War Department; it was later split up among private developers. Hendon Urban District Council acquired some of the land for playing fields and to provide a new home for Hampstead Football Club in 1926 (which became Hendon FC in 1946).

In 1913, the southern part of Clitterhouse farm became the Beatty School of Flying (a joint venture with early American aviator, George Warren Beatty 1887-1955, and Handley Page). This became the Handley Page’s Cricklewood Aerodrome and factory during 1917. Handley Page developed and tested Britain’s first bombers. After the First World War, passenger flights to the continent became popular. In 1929 the Aerodrome was closed, and the land became Laing’s ‘Golders Green Estate’. Jean Simmons, the actress, was brought up on the estate. Shortly after 1926 Hampstead FC (Hendon FC from 1946) rented some of the land from Hendon Urban District, finishing Clitterhouse as a farm. The rest of the land became a public open space. From 1920 to 1938, Cricklewood Studios occupied part of the aerodrome; these were the largest film studios in the UK. To get an idea of the film studios in action: https://www.bfi.org.uk/news-opinion/news-bfi/features/how-make-your-first-silent-movie-count

The Clitterhouse Farm Project

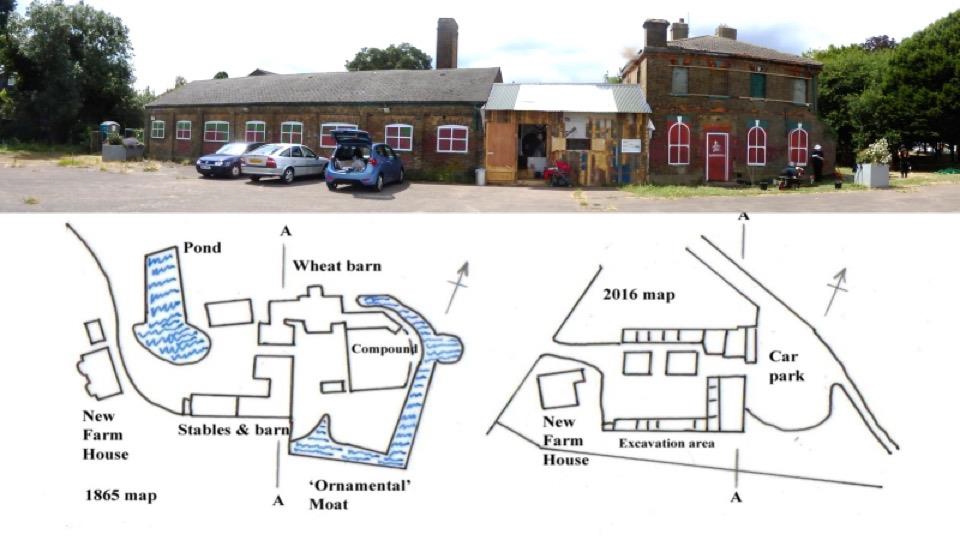

The Clitterhouse Farm Project was founded in early 2013 by local residents – who all live within a five-minute walk of Clitterhouse Farm. They are working to protect the historic Victorian farm outbuildings from demolition and to secure their future, so the entire site can be transformed into a vibrant, creative and sustainable hub that supports the community and small businesses. They wish to provide a compatible and flexible space relevant to the needs of the local population and to create a tangible improvement to the area before, during and after the Brent Cross Cricklewood regeneration. They have secured over £100,000 crowdfunding in December 2018 for community café and workshops including money from the Mayor of London’s Good Growth fund. They are slowly working through the planning stages, as they hope to start on site later this year.

Working closely with the Clitterhouse Farm Project, HADAS members excavated trenches in the garden area to the south of the building in 2015 and in 2016 trenches were dug to the north and along the front of the current buildings. From these we found the foundations of what we believe to be the Wheat barn (see below) and traces of the moat. Our finds include small amounts of pottery from the 12th century along with more extensive amounts from later centuries. The excavations suggest that the older range of buildings should be found under the car park.

The line A–A runs is roughly along the front of the current building as shown in the photo below.

Environmental Samples

Environmental Samples

Mike Hacker collected environmental samples during 2015 dig, the assemblage of pollen and spores (Scaife 2016) were found to be typical of other moats fills. This shows the vegetation diversity of the local human habitats sealed into the ditch or moat. The sources include grassland/pasture; thatching; animal faeces and offal waste (animals fed on hay); and river/stream courses which may have flowed into the ditch. The arboreal pollen is largely oak and hazel, from the wider region and most likely managed woodland, though with birch and elm. Pollen of sedges, grass and willow from damper conditions of the moat associated with a phase of silting/drying out of the moat; perhaps after abandonment. There is a strong representation of cereal pollen: more likely from secondary than local cultivation such as domestic waste – human and animal faeces, offal and from dumped waste food and floor coverings.

HADAS aim to carry out more work over the coming years to expand our knowledge of the development of this important moated farm. With the new café we hope to contribute to a small permanent diplay of material and archaeological finds. Clitterhouse Farm covers more than a thousand years of history from Viking raids, dairy farming, highway robbery, the coming of the railway age, suffragettes, pioneers in aviation for war and commercial travel, early Cinema, the rise of out of town shopping centres and much more. There is still much more to discover.

Bibliography

“Cricklewood High School and Kindergarten”. The Middlesex Courier. 31 July 1891. p. 3. Retrieved 2018-03-17.

Andrea McKenzie, “This Death Some Strong and Stout Hearted Man Doth Choose”: The Practice of Peine Forte et Dure in Seventeenth- and Eighteenth-Century England”, Law and History Review, Vol 23, No 2, Summer 2005

Dr Rob Scaife, Pollen Analysis of Samples from Clitterhouse Farm (CLM15) (007), Visiting Professor of Palaeoecology, School of Geography and Environment, Department of Archaeology, University of Southampton 2016

David Sullivan, “The Westminster Corridor: Anglo-Saxon Story of Westminster Abbey and Its Lands in Middlesex”, 1st January 1994, Historical Publications Ltd

Patricia Warren British Film Studios: An Illustrated History, London: B.T. Batsford, 2001, p.22

Arkley Greyware medieval pottery production, South Hertfordshire Melvyn Dresner

The material found at the Arkley kiln site (Dyke Cottage), Barnet was discovered in 1959/1960 (including a complete pot). The HADAS finds group (led by Jacqui Pearce) help re-package and process the finds in 2014/15. We also undertook some further chemical and petrographic analysis including linking the kiln site with consumer sites. We are in process of writing up this research, as well as continuing to working on other Barnet sites, where this type of pottery was used (e.g. Ye Olde Mitre Inne, Barnet dug by HADAS in 1989). This report is part of this ongoing work.

The Arkley Brick – One piece of kiln furniture returned to the HADAS archive from Barnet Museum by Derek Renn earlier this year, which is part of the evidence of pottery production in Barnet since the 11th century. The material found at the site was medieval greyware – South Hertfordshire. This was mainly waste pottery sherds; material that failed as usable pottery due to production faults, as well as kiln furniture – fire bars and parts of the dome of the kiln. The finds were found in pits cut into the clay. The kiln itself was not found.

Medieval Barnet and wider landscape

The Romano-British tradition (Renn 1964) of pottery manufacture was known along the route of Watling Street between Brockley Hill and St Albans, which is to the north and west of Arkley, though continuity with pottery of 11th century is unlikely. We know St Alban’s Abbey owned the land around the site (Taylor 1995). St Alban’s Abbey, with the shrine of England’s first martyr, became prestigious and important. Throughout most of the medieval period it was England’s premier Benedictine abbey with numerous daughter houses stretching from Tynemouth in the north to Binham near the Norfolk coast. The Abbey was one day’s ride from London. The first Norman abbot was Paul of Caen from 1077 to 1093. By 1100 the Great North Road had been built, with two early settlements at East Barnet and Barnet Gate (or Grendelsgate). The Market charter was granted by King John in 1199. Manor court were sometimes held at Grendelsgate. According to Renn (1964), the Barnet Court Book shows a flourishing community by 1245. He suggests the Potters Lane may date from 1247. Woodland would be split between lord of the manor (St Alban’s Abbey) and peasants who worked the land, would have had rights such as firewood. The potter would need access to fuel (wood, charcoal), water for processing, clay (geology, clearings, glades), the market, organisation, and subsistence. Pottery at Arkley marks the transition from domestic production for use within the household to larger scale production for the market. The rule of Benedict had a particular attitude to craft and the market, which help us understand the potter’s world.

“If there are craftsmen in the monastery, let them practice their crafts with all humility, provided the Abbot has given permission….

If any of the work of the craftsmen is to be sold, let those through whose hands the transactions pass see to it that they do not presume to practice any fraud…

…and in the prices let not the sin of avarice creep in, but let the goods always be sold a little cheaper than they can be sold by people in the world, “that in all things God may be glorified.”

Renn (1964) suggests that the 13th century Arkley kiln would be a vertical kiln, where pots were stood on a platform of firebars radiating from a central support, with hot fumes escaping through a hole in the dome. Domestic refuse includes sheep and ox bones; metal slag; micaschist whetstone, oak, beech and birch charcoal. Wasters that were under fired; dunted; or spalled. Also included building material – such as chimney pots or roof finials. He parallels finds here with South Mymms castle.

Pottery Fabric

The pottery found at Arkley can be classified into four types (SHER 1, 2, 3 and 4). Over seventy per cent of the pottery is course medium oxidised (SHER 3). Around 25% is reduced course ware (SHER 1). Fine ware makes up around 3% of the estimated number of vessels, with 2% reduced (SHER 2) and 1% oxidised (SHER 4). Work continues….

HADAS Finds Group, sorting South Hertfordshire from Ye Old Mitre Inne, Barnet, March 2019

Bibliography

Renn, Derek (1964). Potters and Kilns in Medieval Hertfordshire.

Taylor, Pamela. The Early St. Albans Endowment and its Chroniclers, Historic Research, Volume 68, Issue 166, June 1995

St. Benedict’s Rule for Monasteries http://www.gutenberg.org/files/50040/50040-h/50040-h.html#chapter-57-nl-on-the-craftsmen-of-the-monastery

West Heath mystery, Orkney and HADAS Melvyn Dresner

HADAS has a long link with Orkney and its archaeology, we are trying to locate a missing video.

Daphne Lorimer’s worked with HADAS on the West Heath Mesolithic site, Hampstead during the 1970s and 1980s, which was pioneering – helping to bringing together scientific techniques with community archaeology, lithic analysis and environmental sampling. Daphne was awarded an MBE for her equally impressive role in Scottish archaeology in Orkney and as founder of the Orkney Archaeology Trust. Janet Mortimer has just returned from an archaeological tour with tales of Daphne, and a mystery to be solved. There was a film made at West Heath in 1970s, and where is it now? What we know, is on the HADAS trip in 2000 to the Orkneys, members were shown around by Jane Downes and Julie Gibson. One afternoon included a visit to Daphne’s place ‘Scorradale House’ she had laid on a ‘high-tea’ and some displays including a video of a TV programme made at the West Heath dig of which Daphne was heavily involved and co-author of the dig report. Janet found out that Daphne’s archaeology-related books and reference material went to Archaeology Institute at Orkney College, University of the Highlands and Islands. So far no video. Dudley Miles is visiting Orkney next month on his trip to the Northern Isles. I return for a third season to work at Ness of Brodgar, any clues much appreciated.

More info about Daphne Lorimer here: http://www.orkneyjar.com/archaeology/dhl/dl/index.html and also HADAS newsletter (409 April 2005). Some photos from HADAS dig at West Heath in 1970s.

Surprisingly Rewarding on the Thames Foreshore Catriona Stuart

Catriona Stuart gives her take on Thames foreshore archaeology.

Only 7 miles away from the Quadrant Stone, the biggest available archaeological site in England – the Thames Foreshore, revealed twice a day at low tide. This isn’t news to you. But maybe its availability for archaeological research and its’ urgency because of the rapidly changing foreshore – is! At low tide 5th century fish traps, ancient causeways, river crossings have all been observed. Boats, both building and breaking, smaller craft put to other uses, rituals both old and current (Hindu ceremonies) evidence of all are to be found on the foreshore.

Apart from the Roman Bridge across the river, originally the main traffic along or across the river was by boat. Car boot sales a totally modern invention? Not exactly. Imagine a Briton pulling their boats up onto the Thames foreshore when Romans occupied London and selling their goods in exactly the same way. This happened just upstream of the Londinium – the Roman port was downstream of the Roman wall. Who when stepping over water into an unstable boat who hasn’t worried about dropping something into the water, to be lost beyond retrieval? Nothing has changed.

The collection of fast flowing tributary rivers and canals fusing to become the Thames, finally turns into a wide meandering river flowing over flat lands of thick mud. These dangerous wet mudbanks were made usable by folk who lived on the riversides sinking all their rubbish onto the riverbanks. From offcuts of leather shoes tied in a bundle thrown in at Tudor Greenwich, to the debris from the Great Fire of London. (I am still looking for signs of burn marks on the broken 17th century roof tiles that litter the foreshore under Cannon Street railway arch). Clearly to be seen at Bermondsey and Rotherhithe are the remains of World War Two bomb damaged buildings pushed onto the foreshore!

Once there were slow vessels going through a crowded river, powered by sail or physical rowing docking, mooring tight to one another. There was steam and mechanically powered boats. This, in the life of river traffic was only for a short length of time. Since the change in 1960 to container shipping, and the opening of the London Gateway container dock at Tilbury 30 miles from London, the Thames’ old docklands is now an open river with comparatively little river traffic. The Thames is travelled by large river buses going at speed. The wake from these river buses rapidly runs up the foreshore eroding both it and everything on it. Downstream of Teddington Lock the foreshore is also subject to tidal movement. There is also deposition of mud from the many tributary rivers. So the foreshore is subject to both deposition and erosion at the same time! Hence the constant change of the foreshore from week to week! The Thames, both the river and the foreshore reflects its continued use by humans for well over 2,000 years. Everyone is allowed onto the Thames foreshore.

Digging into the foreshore is NOT allowed without a Port of London permit. Everything taken from the foreshore is subject to the scrutiny of the Museum of London and officially belongs to them. You are likely to find things of amazing interest, however finding something of monetary value is very unlikely. Nevertheless, with all of everyday London life going on unnoticed only a few meters unseen above, standing on the foreshore of the Thames cocooned in silence, while being surrounded by 2,000 years of tangible often visible history is a very, very, special experience, and yours to enjoy. If you would like to learn more contact www.thamesdiscovery.org Port of London www.pla.co.uk shows Tide Tables under the strap line of safety/hydrography.

Cerne Abbey Site Re-Assessed Charles Leigh Smith

Inspired by Mick Aston referring to a village about to be demolished he mentions that its remnant features might become part of a palimpsest. Aston, like W. G. Hoskins, liked maps – if only they could speak! They do speak to archaeologists of the landscape. Historic sites with dispersed structures often remain a puzzle; but, sometimes illuminated by early maps. Charlie Leigh Smith re-assesses Cerne Abbey, in Dorset, part of his Masters course at Birkbeck College, University of London.

The abbey established in 987, situated just north of Cerne Abbas village, was built towards the end of the 10th century religious reform, when secular religious establishments were being replaced by Anglo-Saxon monasteries. By the 12th century, it was taken over by the Benedictines who replaced the early church by a conventional abbey with church, chapter house, etc. The abbey could also be expected to have its own workshops, brew-house, barn(s) etc, thus allowing it to become largely self-sufficient, and private, as required by the Benedictine rule. For Cerne Abbey the problem had always been that with so few buildings remaining after the Dissolution in 1539, it became impossible to know exactly where the abbey once stood. The earliest OS map marked a cross (+) in Beavoir Field, but these locations have often been incorrect. Beavoir Field is bare grass but lies adjacent to the village cemetery.

A few abbey buildings have survived: the main gatehouse (Abbey House), Porch (a fine monumental structure), lodge (possibly a guest-house), and small barn, which lie nearby. Villagers knew that spot finds came from the back of the village cemetery, such as glazed tiles and parts of tomb effigies. The two horizontal cemetery walls suggested these were the remains of an abbey church, and the 3m (12ft) walls at the St Augustine well, might indicate these could be the remains of a South Transept. But these imaginings were based on interpretations without scientific foundation. Firstly, one of the cemetery walls (on the north side) was too narrow and was shown on an estate map dated 1768, to have been a hedgerow. Observation by John Leyland travelling to the abbey in the early 1500’s, when it was standing, noted a chapel over the St Augustine well; what is currently displayed are the partial wall remains of the chapel’s undercroft (possible pump-house). A resistance geophysical survey in Beavoir Field by Bournemouth University (2014/0071), provided evidence for a linear anomalous area under the grassy field but follow up test pitting disallowed by the landlord (Lord Digby); it was a Scheduled Monument. The subject seemed appropriate for further in-depth research.

A License for a geophysical survey was obtained from the Inspector of Ancient Monuments for West England which came with a recommendation to see the abbey in a wider contextual setting. Research used the tools available to the landscape archaeologist i.e. aerial photographs, LiDAR, OS and historic estate maps; relevant documents held at Kew, Victoria County History, and observations from local writers were reviewed and noted, each providing relevant information. But the most valuable evidence was the find-spot locations (Davey et al., 2011), detailed descriptions and layout plans from other known Benedictine monasteries (Greene, 1992), out-houses (Cook, 1961), fishponds (Aston, 1988), the Cerne abbey seal (Kew archive), and observation on the ground in Beavoir field at the western end some distance from a field gate. This last observation identified a faint linear feature on the grass surface, about 15 feet long with something hard beneath the surface. There was also a large square faced ragstone beside it. It was also evident this section of Beavoir Field had once been levelled off from prevailing downhill lie-of-the-land. It turned out this line probably marked the abbey’s west front and suggested the abbey was aligned not exactly East-West, but EbS/WbN, which would have allowed the abbey to fit with earthworks to the east. The abbey seal showed a turret on either side, and by overlaying the topographical map with Muchelney Abbey (of similar date) the location of the spot finds fell exactly where one would expect a Lady Chapel to have been. What the wider survey indicated was a private (inner religious) area, and a working (secular industrial) area for brew-house and outhouses, one likely late Anglo-Saxon.

Interestingly, a chance conversation with Lord Digby told of a time when as a boy he saw a small wheel about 6 feet in diameter set mostly below ground in the Victorian milking parlour – since demolished. This provided the clue to the site for the abbey’s water mill. This location fitted the water channels seen on the 1768 Estate Map, emanating from this spot. It confirmed the abbey’s work area. The 18th century estate map was drawn up for Mr Pitt-Rivers, who had recently purchased the abbey lands, and although he himself never lived in the village, it was he who we must thank for saving the abbey buildings that survive to this day. A meeting with his grandson (Anthony) at his hall in another Dorset town revealed the abbey’s altar, now re-used as a fireplace but whose provenance was carefully labelled. It was looked down from the other side of the room by a large painting of this once eminent Antiquarian. The outcome of this piece of landscape archaeology research was to provide an holistic layout for Cerne Abbey, but which also led to the probable site for the earlier Anglo-Saxon church, and a reasoned argument why it had come to be built in this remote location of Dorset. Hopefully, the puzzle is solved.

Bibliography

Aston, M., 1988. Medieval fish, fisheries, and fishponds in England (Vol. 1). BAR.

Cook, G.H., 1961. English monasteries in the middle ages. London, Phoenix House.

Davey, J., Belamy, P., Le Pard, G., Pinder, C., 2011. Dorset Historic Towns Project, Cerne Abbas Historic Urban Characterisation, Dorset County Council.

Greene, J.P., 1992. Medieval monasteries. Leicester University Publishing.

Architecture of London Guildhall Art Gallery (off Gresham Street) EC2V 5AE

31 May – 1 December 2019 The Guildhall Art Gallery’s forthcoming exhibition brings together works from the 17th century to the present day to illustrate how London’s ever-changing cityscape has inspired visiting and resident artists over four centuries. As part of the six-month exhibition, John Schofield, cathedral archaeologist at St Paul’s Cathedral; Dr Jane Sidell, inspector of Ancient Monuments for Historic England; and Dr David Allen and Dr Simon Elliott, historian and archaeologist respectively, will lead a series of talks on the use of stone, the tradition of bricklaying within London’s architecture, and historical insights from the Great Fire of London.

The Architecture of London will feature 80 works by over 60 artists, drawing from the City of London Corporation’s extensive art collection to examine the rich diversity of London’s buildings and its varied portrayal by artists, including masterpieces by renowned and emerging artists, such as Lucian Freud, Frank Auerbach and Catherine Yass.

More details here: https://www.cityoflondon.gov.uk/things-to-do/visit-the-city/attractions/guildhall-galleries/guildhall-art-gallery/Pages/default.aspx

OTHER SOCIETIES’ EVENTS Compiled by Eric Morgan

Friday 7th June. Doors open 7.30 pm for lecture at 8.00 pm Landscape Archaeology of Northwest London, Sandy Kidd, GLAAS. Jubilee Hall, Parsonage Lane Enfield (close to Chase Side). Visitors are very welcome (£1.50 per person).

Saturday 8th & Sunday 9th June Barnet Medieval Festival 2019, Barnet Elizabethans RFC, Byng Rd, EN5 4NP

Monday 10th June 3.00 pm Beanos, Boozing & Hopping! Memories of the Old East End, John Lynch

Barnet Parish church (St John the Baptist Church, top of Barnet Hill) Cost: £2 (free for Members of Barnet Museum & Local History Society)

Thursday, 20th June. 7.30 pm – 9:00 pm, Mary Wollstonecraft and Mary Shelley in Somers Town – Charlie Forman, Camden History Society, Burgh House

Sunday 23rd June. 12-6pm East Finchley Community Festival has been taking place in Cherry Tree Wood every summer for nearly 40 years.

Friday 28th June, A Treaty of Peace, Today marks 100 years since the signing of the Treaty of Versailles, the most important of the peace treaties which brought World War I to an end. The Stephens Ink Company always maintained the treaty was signed in their ink and you can learn more and view our 1919 Stationery Office copy, Stephens House and Gardens, 17 East End Road, Finchley, London N3 3QE. Telephone 020 8346 7812

Wednesday 3rd July. 5.30pm Brompton Cemetery Catacombs and Chapel Meet just inside the north gate off Old Brompton Road by the Information Centre at SW5 9JE for a tour of the catacombs and chapel at Brompton Cemetery. £10 for members, £12.50 for non-members, including a cup of tea and biscuit in the chapel following the tour www.brompton-cemetery.org.uk

Friday 12th July. Doors open 7.30pm.Geoffrey Gillam Memorial Lecture: Survivors: Surviving World War II Structures in Enfield Ian Jones EAS. Enfield Archaeological Society, Jubilee Hall Chase Side, Enfield, EN2 0AJ. Visitors £1.50.

Enfield Archaeological Society will be returning to Forty Hall this summer from the 16th to 28th of July 2019 to continue our investigation of Henry VIII’s Elsyng Palace. You need to join the society if you would like to dig. Open day 27th July. Check their website: https://www.enfarchsoc.org/

With thanks to this month’s contributors: Roger Chapman, Catriona Stuart, Charles Leigh Smith, and Eric Morgan

Hendon and District Archaeological Society

Chairman: Don Cooper, 59 Potters Road, Barnet, Herts. EN5 5HS (020 8440 4350)

e-mail: chairman@hadas.org.uk

Hon. Secretary: Jo Nelhams, 61 Potters Road Barnet EN5 5HS (020 8449 7076)

e-mail: secretary@hadas.org.uk

Hon. Treasurer: Jim Nelhams, 61 Potters Road Barnet EN5 5HS (020 8449 7076)

e-mail: treasurer@hadas.org.uk

Membership Sec: Stephen Brunning, Flat 22 Goodwin Court, 52 Church Hill Road, East Barnet EN4 8FH (020 8440 8421) e-mail: membership@hadas.org.uk

Join the HADAS email discussion group via the website at: https://www.hadas.org.uk